Fewer patients per family physician in BC is the result of intolerable working conditions

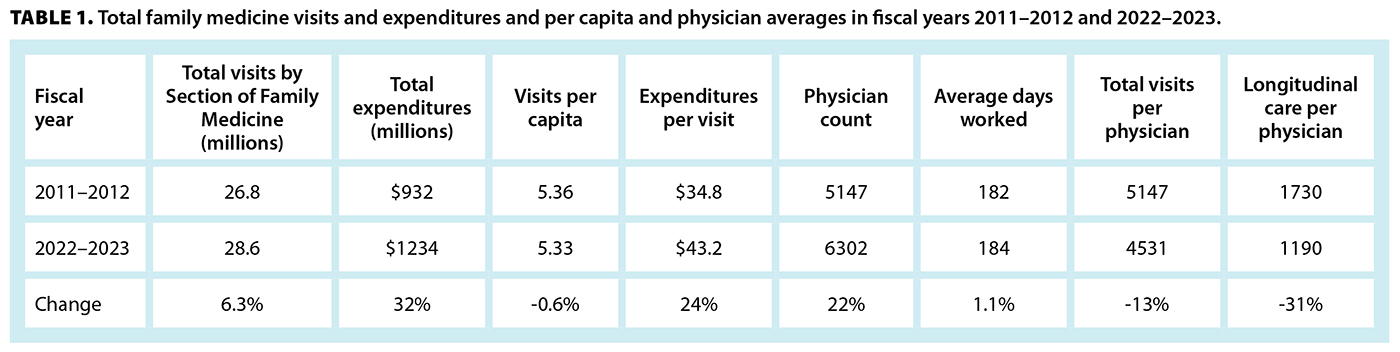

The primary care crisis in British Columbia is characterized by a decrease in the productivity of a family physician. Between fiscal years 2011–2012 and 2022–2023, patients continued 5.34 visits per capita annually, but family physicians provided 13% fewer total visits per physician, including 31% fewer longitudinal care visits [Table 1].[1] For decades, family physicians complained of “intolerable working conditions” and “inflexible payment modalities that do not support multiprofessional practices.”[2] Their complaints ignored, the interaction of a lack of opportunity, inadequate means, and deteriorating motivation caused a decrease in performance.[3] During the same time span, consulting specialists increased their total visits by 17.6%.[1]

The opportunity for family physicians “to perform a task”[3] in the fee-for-service system is the amount of paid time per visit, regardless of the number of disorders managed, unlike for consulting specialists, for whom “service” means managing one disorder. As disease complexity increased, more time was needed per visit but not provided. In 1977, federal funding of health care was reduced from the initially promised 50% to 23%. BC’s Ministry of Health responded by reducing the annual fee-for-service increases to half the annual general inflation rates from 1997 onward.[4] The cumulative effect of that is illustrated by the reduction in constant dollar value of the family medicine in-office visit fee (code 00100) from $17 in 1982 to $32.71 in 2022. At the cumulative general inflation rate of 178.7%, it would have been $47.38 in 2022.[5] The difference of $14.67 represents a 44.9% loss of payment for the service. In 2012, family physicians had the lowest fee-for-service remuneration per average day worked and by 2023 had received the lowest annual increases.[1] That resulted in the ratio of fee-for-service earnings per average day worked of the highest-earning consulting specialist section to the Section of Family Medicine increasing from 3.5 to 4.3, a 23% increase over 11 years.[1] Increases in office staff remuneration and facilities rent in the 1990s and the cost of digitization in the 2000s further reduced after-expense incomes for family physicians.

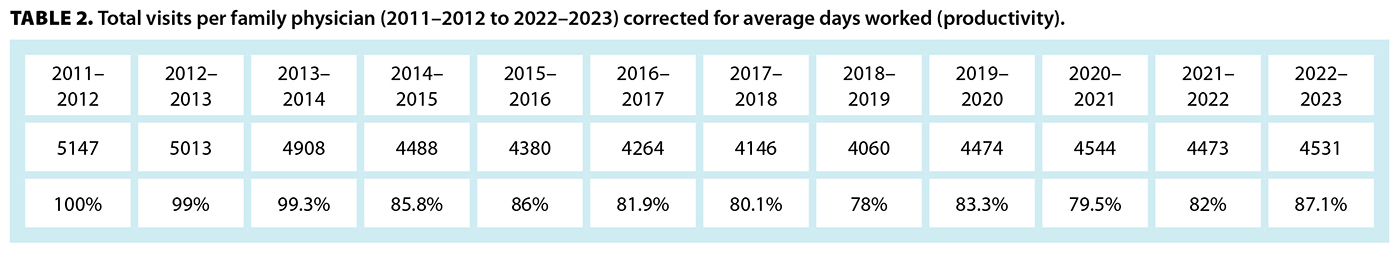

The means to be “capable of performing a task”[3] consists of tools and assistants to improve efficiency. In BC, physician assistants are limited to Ministry of Health–operated clinics; all other clinic types lose out on efficiencies that can double the number of patients per family physician and reduce costs per disorder managed.[6] By fiscal year 2013–2014, family physicians had reached a relatively stable average of 5000 visits per physician annually, but in 2014–2015, there was an unexplained 13.5% decrease in visits, which was never regained [Table 2].[1] In 2014, the UBC Medical Journal reported that most family physicians in BC had adopted electronic medical records (EMRs),[7] drawing attention to published reports that using EMRs takes more time.[8] The increased time per visit decreased opportunity, further reducing fee-for-service remuneration, and caused anxiety, depression, and burnout. The additional hardware and software that was required increased operating costs.

The motivation “to want to perform a task”[3] began to diminish slowly but relentlessly, the three domains interacting to produce a vicious cycle of ever-decreasing morale, motivation, and lost productivity. Proposed alternative explanations for decreased family physician performance, such as feminization, aging, and lifestyle balance, are inconsistent with consulting specialists’ sections not experiencing similar losses of productivity.[1]

A review of BC family physicians’ working conditions, going back to the inception of publicly funded health care in Canada, explains the current crisis in access to primary care. The solution is self-evident.

—Gerald Tevaarwerk, MD, FRCPC

Victoria

hidden

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Ministry of Health, Health Sector Information, Analysis & Reporting Division. MSP physician resource report: 2013/2014–2022/2023. October 2023. Accessed 26 April 2025. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/medical-services-plan/msp_physician_resource_report_20123014_to_20222023.pdf.

2. Thirsk R. The lessons of the Columbia disaster can be applied to my current field of health care. Globe and Mail. 1 February 2025. Accessed 26 April 2025. www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-lessons-of-the-columbia-disaster-can-be-applied-to-my-current/.

3. John A, Newton-Lewis T, Srinivasan S. Means, motives and opportunity: Determinants of community health worker performance. BMJ Global Health 2019;4:e001790. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001790.

4. Barer ML, Evans RG, McGrail KM, et al. Beneath the calm surface: The changing face of physician-service use in British Columbia, 1985/86 versus 1996/97. CMAJ 2004;170:803-807. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1020460.

5. Bank of Canada. Inflation calculator. Accessed 26 April 2025. www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator.

6. Tevaarwerk GJM. Does the longitudinal family physician payment model improve health care, including sustainability? BCMJ 2023;65:242-247.

7. Grewal GS. Electronic medical records in primary care: Are we there yet? UBCMJ 2014;6:15-16.

8. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: A timely motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Int Med 2016;165:753-760. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0961.