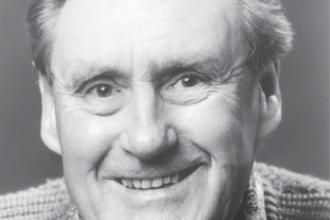

Dr Angus Rae

A pioneer in the care of patients with kidney disease in British Columbia—establishing the Renal Unit at St. Paul’s Hospital, initiating the home hemodialysis program, and traveling the province (and beyond) to treat patients—Dr Angus Rae has spent his long and storied career doggedly fighting his gentlemanly fight for recognition of the importance of the clinician’s role in teaching medicine.

|

| Dr Angus Rae |

In the 30-plus years that I spent at St. Paul’s Hospital I must have gone to more than a thousand medical grand rounds; fewer than a handful of them stand out in my memory. One that does was given by the remarkable man who is the subject of this article.

Dr Angus Rae was born in 1929 in London, UK, the first child of his radiologist father and nurse mother. He had an unremarkable childhood until life was disrupted by the onset of war. When bombing began in London he and his younger brother were sent to schools deep in the English countryside, safely tucked away from the usual bombing corridors. Still, every time the sirens sounded students had to take shelter—a highly exciting activity for a young teen Angus. One of his standout memories from the time is being sent back to London by ambulance due to onset of acute glomerulonephritis, though he insists this did not trigger his interest in kidneys.

Dr Rae entered the London Hospital Medical School (now the Royal) in 1947 at age 18. Of approximately 80 students, only five or six were women. Meanwhile 80% were ex-servicemen who were much older, wiser, and more battle-worn than he. After completing his studies, Angus carried on with the usual licensing requirements (6 months’ medicine/6 months’ surgery), and then came compulsory military service. While waiting for a posting, Angus and a few young classmates completed parachute training with the Airborne Brigade but never had to jump in conflict.

When the posting finally came, he spent 2 years in Malaya (Malaysia) caring for British Gurkha troops and their families, happily supervising 250 births along with three excellent midwives and limited antibiotics—penicillin, sulpha, and tetracycline. He had many interesting medical encounters, a 6-week hike in the mountains of Nepal, and a trip with Fijian troops (also serving in Malaya) across the border to play and win a few rugby football matches in Thailand.

Finally in 1956 he was promoted to major in medical charge of retiring soldiers and sent home on a troop ship via Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Bombay (Mumbai), and Aden (Yemen). How the world has changed!

|

| L–R: Dr Angus Rae in Malaya in 1956 with nurses Domashiring Llama (Tibet), Sabitri Devi Tamang (Nepal), Matilda Mamon (India), and Dr Vincent Sweeney (Scotland). |

Once back home, Angus had to decide what to do with the rest of his life, but before he had made up his mind he was called up from the reserves to the Suez Canal conflict. Fortunately that ill-fated fight was short-lived and he returned home again, convinced that he wanted to study internal medicine. After a number of interviews he was offered a position in cardiology at the Royal Free Hospital, having been interviewed by Professor Sheila Sherlock and others. Until this day he is not sure if the deciding factor was that he played rugby, as there was intense sporting competition between the eight medical schools in London!

During his training, interest in the new field of hemodialysis was increasing, despite many “experts” considering it to be a waste of time, money, and resources. Detractors aside, Professor Sherlock (a liver specialist) encouraged one of her research fellows, Dr Stanley Shaldon, to start a renal unit. Angus became involved and joined the unit in 1962, thus beginning his lifelong interest in the kidney and its diseases.

In the mid-60s, at a meeting of American nephrologists organized by his professor in London, Angus was offered a job in San Francisco. Always looking for adventure, he accepted and took his right-hand-drive car with him on the boat, planning to drive across the continent. He advertised for someone to drive with him to share the cost, and chose Prudence, a muscular, over six-foot-tall Australian sheep farmer who was not intimidated by the unusual car. Sitting in what would be considered the driver’s seat, reclined, with her feet on the dash, she more than once caused the pair to be pulled over by police, who collapsed with mirth when they saw Prudence sleeping in the sun.

After a year at the University of California in San Francisco, the University of Washington in Seattle beckoned, and from there Professor Belding Scribner, a world leader in dialysis, sent Angus to Spokane to supervise one of the world’s first home hemodialysis training programs, which the professor had recently set up.

While Angus was learning about this relatively new field of medicine, over the border Dr Bill Hurlburt was looking for someone to start a similar program at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. Angus’s name was suggested by a medical school classmate, Dr John Kerridge. Angus accepted, came to Vancouver in 1968, and went right to work. He didn’t even ask what he would be paid. He was later told that until he could make $1000 per month in the fee-for-service system he would be paid up to that amount by St. Paul’s. It took Angus 8 months to reach that threshold, and thereafter he survived on his own. He and his later appointees made their living on fee-for-service payments, pooled their income, and were never on the payroll of the hospital or the Faculty of Medicine except for responsibilities outside of patient care, such as lectures.

Soon after arriving in Vancouver Angus arranged for nurses from St. Paul’s to visit Seattle and learn how best to train patients to do their own hemodialysis at home. The training was immediately implemented when the nurses returned to St. Paul’s, and within 3 months two patients were trained and sent home to do their own hemodialysis, the first in BC.

By the end of the 1970s, the division had expanded to include Drs Clifford Chan Yan and Ronald Werb, then Paul Taylor, and later Tony Chiu, each of whom brought new ideas. The first, Dr Chan Yan introduced internal jugular catheterization, not only of value for blood access in acute renal failure, but also for total parenteral nutrition, so the unit took charge of those who needed this in hospital and at home.

In the late 70s there was pressure to start renal transplantations at St. Paul’s, but this took them until 1986. The success was in large measure due to the appointment in 1984 of Dr David Landsberg, a transplant physician trained in eastern Canada. They were also fortunate to have a urologist, Dr David Manson, ready to take this on with enthusiasm. In another of life’s coincidences, a member of the Ministry of Health was a diabetic with early renal failure unknown to his colleagues. He suspected he would be more likely to get a transplant if St. Paul’s was given permission to start renal transplantations, which they were, and he did.

In 1986 their first transplant was performed on a 34-year-old male who is still alive with normal kidney function, having required a second transplant some years later. The program proved very successful, doubling the transplantation rate in BC in 3 months and tripling it in the first year. St. Paul’s continues to have one of the leading programs, now listed among the top in numbers across the country.

The seed that Angus planted in 1968 has grown into a leading centre for the treatment of kidney disease across the land, with the vision to initiate new programs such as the Travellers’ Dialysis Clinic (TDC)—inspired by Expo 86 for dialysis-dependent but otherwise healthy visitors from other provinces and overseas (local units were too full to take them as patients). As for advances in transplants, a paired exchange program and a living anonymous donor program have been initiated just to name two.

Nephrology was a small field when Angus came so he offered to consult on patients in several towns across BC and in Whitehorse, Yukon, where there was no general internist in residence, thus saving the towns money and increasing the number of renal patients for the unit at St. Paul’s.

Many of these communities eventually obtained their own internists, except Whitehorse, where Angus did his last clinic in 2007, 12 years after he had retired. In the 35 years of service to Whitehorse alone he did over 2000 consultations, in many cases saving patients and the medical system the expenses involved in having to be seen in major cities. This service to rural BC and Yukon was invaluable and set the standard for these clinics to this day.

Over the years, Angus gave many lectures, but none were as important, well received, and widely acclaimed as his 1990 Osler Lecture, which was subtitled the Rise and Fall of Bedside Medicine. The importance of a clinician’s role in teaching medicine remains Angus’s passion to this day and was instrumental in the part he played in the formation in 1998 of the University Clinical Faculty Association (now the Doctors of BC Section of Clinical Faculty).

Angus has written widely on diverse topics, from how to give bad news to patients to a report from the 1998 World Transplant Games in Sydney, Australia.

Building the Renal Unit at St. Paul’s is Angus’s major accomplishment, starting from virtually nothing in 1968, when he was alone but for excellent nurses and technicians. Patients were gathered from across BC and new physicians were appointed who together pooled their largely fee-for-service income, each taking a percentage according to seniority, paying for secretarial services, and buying their offices—initially just a hole in the ground and now elite studios from where they supervise the ever-expanding hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplant services in the Renal Unit at St. Paul’s.

The group’s last appointee before Dr Rae left was Dr Adeera Levin in 1990. She is now head of the UBC Division of Nephrology working from St. Paul’s and in 2015 was appointed to the Order of Canada for “her tireless work on behalf of people with kidney disease, both nationally and internationally.”

From 1971 to 1981 Angus was in charge of the rotating internship program at St. Paul’s, reputed to be one of the best of its kind, gathering students from many countries, including a woman from Chile escaping Pinochet’s dictatorship. Angus thinks it is unfortunate that this system of training students by giving them a broad view of medicine from which to choose their future has been abandoned.

From 2006 to 2015, Angus continued to be involved in his work. He supervised students in the annual problem-based learning course on kidney matters (the last session of which took place on his 86th birthday). With the cash he received for this he established the Angus Rae Aboriginal MD Bursary to help increase the number of Indigenous students enrolling in our medical school.

Angus is especially proud of receiving the Kidney Foundation of Canada’s Annual Award, being made a senior member of the CMA, being honored as clinical professor emeritus of medicine and given honorary alumnus status at UBC, his time as the American College of Physicians’ governor for the BC chapter, and perhaps above all, having taught and mentored students from the day he arrived. He seems especially proud of the many letters of thanks they have sent him.

|

| Dr Angus Rae with his wife, Dr Ann Skidmore, receiving the BCMA Silver Medal of Service at the Victoria Conference Centre (1998). |

Angus is now happily retired in Victoria but is not idle. He continues to visit Yukon, having been granted honorary privileges at Whitehorse General Hospital for his many years of service.

He is a vocal advocate for an equal partnership between the academic culture of UBC’s Faculty of Medicine and the clinical culture of those dedicating their lives to the care of patients. Such a union he believes is the only way to help our ailing medical system.

Most recently Angus encouraged me to vote for his favorite candidate in the election of the next president of Doctors of BC! He has been happily married to his wife, Ann, for many years and they have been blessed with children and grandchildren.

As for the title of Dr Rae’s grand rounds that fascinated me? It was “Evolution: How the Mammal got its Nephron.”

hidden

Dr Lawson is a retired member of the BCMJ Editorial Board. She practised respiratory medicine at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver from 1982 to 2010. Like Dr Rae, she is happily retired in Victoria.