Addressing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in BC: Practical approaches

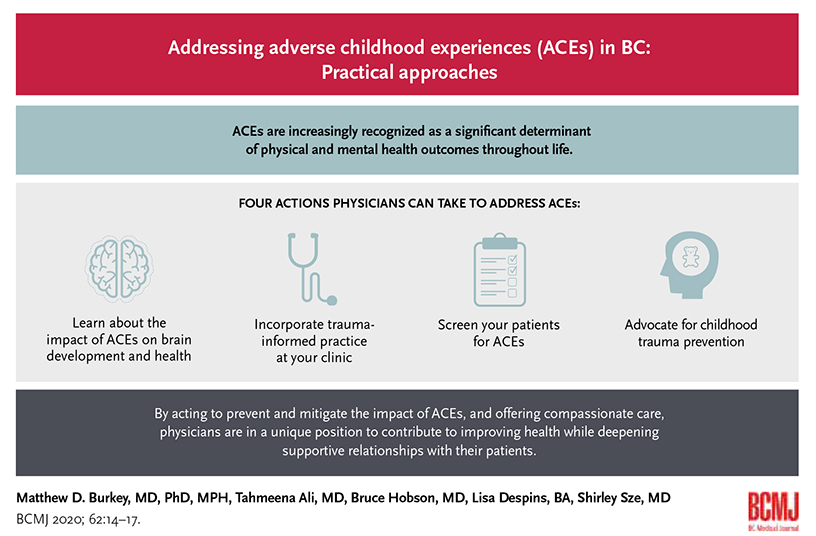

ABSTRACT: Childhood experiences are increasingly recognized as a significant determinant of physical and mental health outcomes throughout life. Presentations at the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Summit 2019 highlighted activities underway to address ACEs through the four priority actions developed after the ACEs Summit 2017: (1) promote cross-sectoral leadership, (2) implement proven interventions to prevent childhood adversity and promote resilience, (3) strengthen policies to “build better brains and build better lives,” and (4) implement brain science and trauma-informed training across all sectors. As clinicians and respected experts, physicians can address ACEs in their practices and communities by learning about the impact of ACEs on brain development and health, incorporating trauma-informed practice in their clinics, screening their patients for ACEs, and advocating for childhood trauma prevention and improved services for those affected by ACEs. By providing compassionate care and acting to prevent and mitigate the impact of ACEs, physicians can improve health outcomes and deepen supportive relationships with their patients.

Physicians can mitigate the impact of past traumatizing events on their patients and society by incorporating trauma-informed practice in their clinics and advocating for childhood trauma prevention.

On 9 May 2019 the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Summit 2019 was hosted by the Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use (CYMHSU) Community of Practice, an initiative of the Shared Care Committee (a Doctors of BC and BC government joint collaborative committee). The summit brought together over 500 physicians, allied health professionals, education representatives, and government leaders from across BC to provide updates and spur action on addressing ACEs.

ACEs defined

Adverse childhood experiences are traumatizing events that occur during childhood and adolescence. To date, research has focused primarily on three broad categories of ACEs: abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual), neglect, and household dysfunction (e.g., divorce, parental conflict, substance abuse).[1] Exposure to ACEs without adequate support leads to prolonged activation of the body’s stress response systems. The sustained activation of stress response systems resulting from ACEs has been shown to cause long-term changes in cortisol reactivity and immune function, and to affect development of brain structures essential for learning and memory.[2]

The term “adverse childhood experience” came into use in the late 1990s after a landmark epidemiological study of over 9000 adults brought the issue into the public health spotlight.[3] This study in a primarily white, middle-class population in California (and a number of subsequent studies in other populations) found that ACEs are common: more than half of participants reported at least one ACE, and a quarter reported two or more. Results of the study demonstrated dose-response relationships between the number of ACEs and higher rates of multiple health behavior risk factors, mental health and substance use disorders, and chronic diseases, including cancer, heart disease, stroke, and COPD. For example, individuals with exposure to four or more ACEs had a fourfold to twelvefold increased risk of drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts.[3] Individuals with six or more ACEs died nearly 20 years earlier than those with no reported ACEs.[1]

In addition to individual health and emotional impacts, ACEs have societal impacts. Adolescent and adult survivors of child abuse and neglect are more likely to perpetrate acts of violence, crime, and aggression.[4] A recent meta-analysis estimated that ACEs account for 41% of the population-attributable risk for substance use disorders in North America.[5] The same meta-analysis estimated the total annual economic costs of ACEs in North America at US$748 billion, with most costs (more than 75%) resulting from patients with two or more ACEs.

Given the prevalence of ACEs and the many negative health, emotional, and societal impacts, an important question emerges: what can be done about ACEs? At first glance, these past traumatizing events do not appear to be amenable to intervention. Indeed, once an ACE has occurred, it cannot be reversed or “fixed.” However, evidence is emerging from scientific studies and clinical practice that ACEs can be prevented and their harm mitigated, including in primary care settings.[6] Moreover, those affected by ACEs often suffer in silence and benefit greatly from compassionate, caring, and understanding interactions with others. This applies especially to interactions with health care professionals.

Addressing ACEs in BC

Two ACEs summits hosted by the CYMHSU Community of Practice in November 2017 and May 2019 brought together experts, clinicians, policymakers, and people with lived experience of ACEs to share promising practices and build coalitions to address ACEs in BC.

Several ACEs Summit 2019 presentations highlighted activities underway to address trauma through the four priority actions identified in the consensus statement[7] developed after the ACEs Summit 2017: (1) promote cross-sectoral leadership, (2) implement proven interventions to prevent childhood adversity and promote resilience, (3) strengthen policies to “build better brains and build better lives,” and (4) implement brain science and trauma-informed training across all sectors [Table].

What physicians can do

In BC and elsewhere, physicians are advocating for trauma prevention and implementing ways to support their patients affected by ACEs. Identifying ACEs in patients can sometimes help explain poor treatment responses to ongoing physical and mental health issues. Physicians are also able to develop a more empathetic approach to patients undergoing stressful care situations when they recognize that growing up in a dangerous setting can lead to behaviors such as agitation, withdrawal, and defensiveness. Understanding a patient’s past experience and responding appropriately to the consequent behaviors helps to deepen the therapeutic relationship with such a patient. In fact, compassionate relationships are central to preventing and treating ACEs in both children and adults.[8] Changes to the physician’s approach and the treatment setting, as well as to trauma-specific interventions, can aid healing and improve outcomes for patients affected by ACEs.

Trauma-informed practice creates treatment settings that help instead of harm and provides a framework for approaching patients affected by ACEs or trauma during adulthood.[9] Trauma-specific treatments such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) can help reduce psychological symptoms and improve functioning in patients experiencing significant mental health symptoms such as posttraumatic stress disorder related to ACEs.[10]

At the population level, prevention presents the greatest opportunity to address ACEs, which persist largely through intergenerational patterns. Some risk factors for ACEs, such as parental mental illness and substance use disorders, present treatable target conditions in health care settings. A number of preventive interventions—from parenting education to community preschools and high-quality early childhood programs—have demonstrated effects on lowering rates of child abuse.[11] However, the largest and broadest community-wide impact on ACEs comes from addressing underlying social determinants of health such as poverty, food security, education, discrimination, and safe housing.[12] Economic modeling suggests that investments in prevention could result in large benefits to population health and the economy: a 10% reduction in ACE prevalence in North America would lead to a corresponding reduction of 1 million disability-adjusted life-years equivalent to savings of US$56 billion.[5]

So what specific steps can physicians take to prevent and mitigate the effects of ACEs? Physicians can learn about the impact of trauma on brain development, incorporate trauma-informed clinical practice in their work, screen patients for ACEs, and advocate for childhood trauma prevention (see Resources).

Learn about the impact of trauma on brain development and health. There was broad consensus at the ACEs Summit 2019 that learning about the impact of trauma on brain development, behavior, and health outcomes is a critical first step for all practitioners in health, education, and social services. Understanding the role of ACEs in the “difficult” behaviors of those around us—both patients and co-workers—can lead to greater compassion and better care.

Incorporate trauma-informed practice at medical clinics. Given the prevalence of ACEs and the effects of other forms of trauma (e.g., colonization, stigmatization, discrimination), a proactive “universal precautions” approach can help make the medical clinic a psychologically safe, healing space for all patients. Trauma-informed practice is based on four principles:

- Trauma awareness.

- Emphasis on safety and trustworthiness.

- Opportunity for patient choice, collaboration, and connection.

- Strengths-based approach and skill-building.[9]

These principles should be considered by physicians and clinic staff.

Screen patients for ACEs. Screening for ACEs as part of comprehensive history-taking is becoming a common clinical practice and is reported to be well received by patients. Identifying ACEs helps physicians understand a critical contributor to health behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes. Moreover, patients often report that when a clinician asks about ACEs it demonstrates an interest in their past experiences. Screening tools can be incorporated into routine office procedures and may be of particular use at prenatal appointments for early identification and support during a critical period, and for patients with complex chronic diseases. While time constraints are often cited as a barrier to screening for ACEs, a study of clinics that routinely screened for ACEs found that fewer than 10% of patient encounters were prolonged by more than 5 minutes when trauma was identified.[13]

When patients report ACEs, physicians can respond with compassion and then listen (e.g., “It sounds like you went through some rough times as a child. I’m really sorry that happened. That should never have happened to you. How do you think your experiences are affecting you now?”). Physicians can also determine what trauma-specific treatments are available through local community organizations and public service agencies (e.g., the Canadian Mental Health Association, health authority mental health centres, child and youth mental health teams of the Ministry of Children and Family Development).

Advocate for childhood trauma prevention. Finally, physicians can be effective advocates to bring about greater understanding of ACEs and develop resources for prevention and supports in their communities. Physicians are well positioned to educate their communities and clinic colleagues and staff about the health and developmental impacts of ACEs.

Support for physicians

In BC the CYMHSU Community of Practice supports physicians with local education initiatives and unifies the physician voice to advocate at the provincial level. The Community of Practice also networks, shares information, and engages in online discussions via webinars and the Slack platform (https://slack.com/intl/en-ca/features). As well as taking advantage of CYMHSU resources, physicians can create self-healing communities where they live and work. A self-healing community intentionally uses culture and strengths to collaboratively build a sense of belonging, as seen in Cowlitz County, Washington, where many health and social problems were overcome after the county “held education events to learn about the science of adversity, hosted networking cafés, organized neighborhood residents and linked service strengths across disciplines.”[14]

Summary

ACEs are common and can lead to premature death and disability, both of which affect individuals, families, and society.[4,5] The ACEs summits in BC in 2017 and 2019 have highlighted system-level priority actions to address the impact of childhood trauma: (1) promote cross-sectoral leadership, (2) implement proven interventions to prevent child adversity and promote resilience, (3) strengthen policies to “build better brains and build better lives,” and (4) implement brain science and trauma-informed training across all sectors.

The scientific literature indicates that caring, connected relationships—in both personal and professional spheres—along with evidence-based prevention and treatment interventions make a difference. Physicians can play a major role in addressing ACEs: both in the clinical work they do and in their broader roles as advocates, citizens, family, and community members.

Competing interests

None declared.

Resources for addressing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

Learn about the impact of trauma on brain development and health

- Join an ACEs 101 webinar through the Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use (CYMHSU) Community of Practice. Contact ejanel@doctorsofbc.ca to sign up.

- Enroll in the free online Brain Story Certification course: www.AlbertaFamilyWellness.org/training.

- Look into the science of toxic stress provided by the Center on the Developing Child: https://developingchild.harvard.edu.

Incorporate trauma-informed practice at your clinic

- Review practical tips and scripts on communicating in a trauma-informed manner: https://equiphealthcare.ca/key-resources.

- Implement changes with the help of the Trauma-Informed Practice Guide: www.bccewh.bc.ca/2014/02/trauma-informed-practice-guide.

Screen your patients for ACEs

- Use the ACE Questionnaire to find out if a patient has had an adverse childhood experience: www.ncjfcj.org/sites/default/files/Finding%20Your%20ACE%20Score.pdf.

- Adapt the resource developed by the Kootenay Boundary Division of Family Practice, Adverse Childhood Experiences—A Toolkit for Practitioners, for your context: https://divisionsbc.ca/sites/default/files/Divisions/Kootenay%20Boundary/ACEs%20Booklet%20v5_Electronic.pdf.

Advocate for childhood trauma prevention

- Join the CYMHSU Community of Practice to advocate with other BC physicians: www.sharedcarebc.ca/our-work/spread-networks/cymhsu-community-of-practice.

- Form a local task force to create a self-healing community in your area: www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2016/06/self-healing-communities.html.

- Review the Centers for Disease Control recommendations for preventing ACEs: www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/CAN-Prevention-Technical-Package.pdf.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

1. Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:389-396.

2. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain: Working paper 3. Updated edition January 2014. Accessed 18 November 2019. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_Developing_Brain-1.pdf.

3. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245-258.

4. Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, et al. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009;373(9657):68-81.

5. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, et al. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e517-e528.

6. Flynn AB, Fothergill KE, Wilcox HC, et al. Primary care interventions to prevent or treat traumatic stress in childhood: A systematic review. Acad Pediatr 2015;15:480-492.

7. Shared Care. Consensus statement: To build better lives we need to build better brains. November 2017. Accessed 18 November 2019. www.sharedcarebc.ca/sites/default/files/ACES%20CONSENSUS%20STATEMENT%20%28ID%20151648%29_0.pdf.

8. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Young children develop in an environment of relationships: Working paper 1. Updated and reprinted October 2009. Accessed 18 November 2019. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2004/04/Young-Children-Develop-in-an-Environment-of-Relationships.pdf.

9. BC Provincial Mental Health and Substance Use Planning Council. Trauma-informed practice guide. May 2013. Accessed 18 November 2019. http://bccewh.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/2013_TIP-Guide.pdf.

10. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

11. O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

12. Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health 2010;100:590-595.

13. Glowa PT, Olson AL, Johnson DJ. Screening for adverse childhood experiences in a family medicine setting: A feasibility study. J Am Board Fam Med 2016;29:303-307.

14. Porter L, Martin K, Anda R. Self-healing communities: A transformational process model for improving intergenerational health. Princeton NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2016. Accessed 18 November 2019. www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2016/06/self-healing-communities.html.

Dr Burkey is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of British Columbia. He is also a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Williams Lake and medical lead for Child/Youth Mental Health, Northern Health. Dr Ali is a full-service family physician in South Surrey. She is also chair of the White Rock–South Surrey Division of Family Practice, and a clinical instructor in the Department of Family Medicine at UBC. Dr Hobson is a retired family physician and medical director of UBC CPD Program Services and the Health Data Coalition. Ms Despins is a communications officer for the Shared Care Committee, Doctors of BC. Dr Sze is a family physician and a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Practice at UBC. She is also chair of the ACEs Working Group of the Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use (CYMHSU) Community of Practice. Drs Ali, Burkey, Hobson, and Sze are all active members of the ACEs Working Group and were involved in planning the ACEs Summit 2019.

EXCELLENT