Psychiatrist + mathematician = best seller

How did a psychiatrist and self-described nondescript writer from Maple Ridge become number three on India’s best-seller list?

The story behind the book Super 30: Changing the World 30 Students at a Time

|

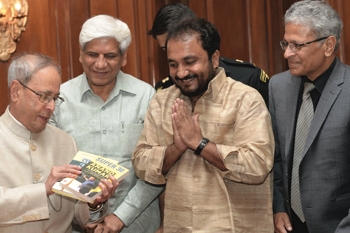

| L-R: The President of India (July 2012-July 2017), The Honorable Pranab Mukherjee, receiving a copy of the book at the presidential palace Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi, (unidentified), Mr Anand Kumar, Dr Biju Mathew. |

How did a psychiatrist and self-described nondescript writer from Maple Ridge become number three on India’s best-seller list? Well, there is no short answer to this question. Dr Biju Mathew, the president of the BC Psychiatric Association, shared his story at the 29 October 2016 Educational Update and AGM. His presentation, “Adversity, Deprivation, Trauma and . . . Success,” covered the genesis of a book, the writing and publishing process, and the many adventures along the way.

Dr Mathew wrote Super 30: Changing the World 30 Students at a Time over three and a half years and signed a publishing deal with Penguin Books India when 50% of it was complete. The book is about a brilliant man named Anand Kumar, who, in the face of overwhelming odds, became one of India’s top mathematicians and founder of Super 30, considered one of India’s most exceptional and charitable schools. The school is located in Patna, the capital of Bihar province, one of India’s most impoverished in every way—educationally, income- and violence-wise, with rampant caste-based conflicts.

Every year since 2002, Super 30 prepares 30 students from the most economically backward areas of the country to enter the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), India’s counterpart to MIT. IITs are a magnet for the best and brightest minds. Many graduates become CEOs of multinational companies. The entrance exam is considered one of the toughest in the world, and odds of getting in are very slim. Data from 2015 reveal that about 1.3 million students take the IIT exam (now called the Joint Entrance Examination—Main) for 9880 positions.

In 2012 Dr Mathew, originally from India’s tropical coastal province of Kerala, and president of the Ridge Meadows South Asian Cultural Society (in Maple Ridge – Pitt Meadows, BC), was looking for a new way to raise funds for the Ridge Meadows Hospital Foundation. Hosting an educational lecture was what he had in mind. He stumbled across a Globe and Mail article about a man from the slums of Patna, India, who went on to become a global celebrity and one of the most recognized faces in India apart from Bollywood stars and politicians—Mr Anand Kumar.

Dr Mathew was uncertain if Mr Kumar would accept an invitation to visit him in Maple Ridge, but extended his invitation anyway. “Please come down and help us; we would like to hear from you. We are a very small organization, but we have a big heart.” Mr Kumar accepted the invitation, but there was some resistance—possibly because he might not be fluent enough in English and people would not understand him. Despite the skepticism, in 2012 he delivered a fantastic 25-minute motivational speech, which was followed by a 10-minute standing ovation.

As a guest in Dr Mathew’s home, he and Dr Mathew spent a lot of time together over the next 3 days. Dr Mathew was touched by Mr Kumar’s tales of deprivation and trauma. Mr Kumar was a member of the lower caste of India, growing up with a strong view of a caste-based society. This visit led to the genesis of the book and was the beginning of a very close friendship. Mr Kumar refers to Dr Mathew as Biju bhai—“brother” in Hindi.

While Mr Kumar’s story had been covered by news media (Newsweek, Time, and a documentary on Discovery Channel), nobody had written a book about him, though three people had tried unsuccessfully. Mr Kumar and Dr Mathew decided that Dr Mathew would write the book.

As head of Ridge Meadows Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry, and during his years in practice, Dr Mathew had come across many patients who faced great adversities, but nothing compared to Mr Kumar’s story. To truly understand Mr Kumar and write about his life, the doctor knew he needed to travel to India. And he did, twice. Dr Mathew morphed into a roving reporter, delving into the roots of Mr Kumar’s life and collecting a tremendous amount of data.

Accompanied by two bodyguards carrying automatic weapons, he visited Mr Kumar’s birthplace, a house in the middle of the slums of Patna. Mr Kumar’s grandfather was a village doctor who studied traditional medicine in high school and bartered his services for grains and eggs. Before Mr Kumar was born, there were eight premature deaths in the family. As well, the family suffered significant financial burden, with six people living in a small two-room house all supported by the father’s income of 600 rupees a month (equivalent to $10) as a postal employee.

Despite these circumstances, Mr Kumar was an exceptional student with rare math abilities, and he managed to get into college and publish several papers in international mathematics journals. He was accepted into the University of Cambridge, in England, but was unable to go because he couldn’t afford it. His dream came crashing down. And then tragedy struck—Mr Kumar’s beloved father died from a massive heart attack. With the loss of his father’s income, the family faced starvation. To survive, Mr Kumar’s mother began to make papadums, a savory Indian snack. She made hundreds of them, and Mr Kumar sold them door to door on two wheels to eke out 10 rupees a day. And then at the age of 19, in 2002, Mr Kumar set up a school for underprivileged students called Super 30. It was one way of dealing with heart-wrenching disappointments.

The school expanded and became a phenomenal success. However, Mr Kumar and the school were not immune to fierce jealousy in the slums. Other tutoring schools charged substantially more for tuition and tried to eliminate Super 30 from the scene. One night, a member of the “coaching mafia” forcibly entered Mr Kumar’s house and stabbed a Super 30 staff member in the abdomen. He nearly bled to death. He was discharged from hospital after a month-long stay, where his 30 devoted students kept vigil 24-7.

Dr Mathew wondered how, despite so many adversities, Mr Kumar could be so successful, especially as a teacher. He taught in a rudimentary one-room shack with a tin roof, a couple of ceiling fans, a blackboard, and a basic loudspeaker. Dr Mathew studied his approach to teaching and spoke with Mr Kumar’s students, teachers, and friends to discover his secret.

He noticed how Mr Kumar, when solving math problems, would engage with students in a nonstop dialogue and with his characteristic zeal. Not ordinary math problems—ones that were based on Mr Kumar’s own real-life difficulties. He wouldn’t provide the answers. He’d press students to come up with four or five different solutions. The exercises were gripping and solved in groups only. Students studied 14 hours a day, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the classroom and then in the evening when Mr Kumar was available since he lives right next door.

There’s a lot to be said about the power of a no-tech one-room schoolhouse in today’s hyperconnected world. No smart phones, no TV, no social media. Dr Mathew was stunned there were no computers. One student told him, “Sir, computers do not provide solutions to our problems. We have to do it ourselves.”

The motto “There is no health without mental health” is also relevant at Super 30. Going to the movies and Diwali celebrations together—socializing as a group outside of school—encourages the students to bond. And through motivational pep talks, Mr Kumar helps build the students’ self-worth. The students may be from the most impoverished backgrounds, but they’re reminded that they’re master problem-solvers, the best and brightest, and can achieve anything with desire and determination. As Mr Kumar says in Super 30:

Education remains the most powerful weapon to tackle most of the world’s problems today, as most of the problems have their genesis in poverty and ignorance. Super 30 is a step toward eradicating this . . . No matter how violent the storm, the ship can emerge with the grit and guidance of a deft hand.

Tuition for Super 30’s 1-year program is free—it is funded by Mr Kumar from fees received by his other school, the Ramanujan School of Mathematics. Clothing, housing, and food are also provided for free during the program. Mr Kumar does not accept any funds from external sources. His mother looks after the students, mainly teenage boys, who love her vegetarian food of roti, rice, and vegetables: no meat, but three square meals a day—something the students could have only dreamed of before. Some students also feed cattle or sell vegetables on the roadside or do other mundane jobs. They consider themselves incredibly fortunate.

The day of reckoning for Super 30 was 30 May 2008—the most important day in the school’s history: 30 out of 30 cracked the IIT entrance exam. No other institution has matched Super 30’s astonishing success rate.

Prior to the publication of Super 30, the extent of Dr Mathew’s writing was psychiatry-related. With the story of Mr Kumar and his school, Dr Mathew was faced with the challenge of a new genre and the pressures of manuscript deadlines. The psychiatrist chuckled as he told his colleagues how he had never written a book in his life, and writing one page could take 5 hours. He had help from a writing team: Mr Arun Kumar, a senior journalist for the Hindustan Times; Mr Robert Prince, a local journalist from Maple Ridge; and Ms Radhika Marwah, the editor at Penguin Random House India. They also helped him navigate the editorial process. The book went through eight rounds of editing and two legal reads before being published. He received daily calls from Ms Marwah, some at midnight, prodding him with deadlines and inquiring, “Dr Mathew, where did you get this data from? Can you clarify this?”

The book was first published in English, translated into Hindi, and then launched in June 2016 in Bihar to much fanfare in front of a huge crowd—so huge, in fact, that Dr Mathew was warned not to go outside the venue for fear he’d be mobbed by around 3000 people. This was all a huge surprise to Dr Mathew, and clearly not something he set out to do. He’s tickled and amazed that his paperback is listed alongside the billionaire inventor Mr Elon Musk’s best seller. Admittedly, the pinnacle of Dr Mathew’s writing career was meeting Honorable President of India Shri Pranab Mukherjee at the presidential palace.

Dr Mathew’s 80 psychiatry colleagues, who each received a signed copy of the book, wanted to know about the glaring absence of his name on the book cover. “It’s not my story,” he says. “It is Anand’s story. My name is on the second page.” He also adds that he did not write the book for personal profit; he really just wants people to read it. It is currently available in English with translations in Hindi, Marathi, and Tamil. All proceeds from its sale go to Mr Kumar for the development and expansion of Super 30. The biggest reward for Dr Mathew is knowing that Super 30 graduates will be free from a life of abject poverty, fulfill their potential, and succeed in the future, perhaps far more than he ever will.

The book hit the Bollywood milieu like a whirlwind. Dr Mathew has received offers for the full rights. Discussions are underway for making a Hindi movie based on Mr Kumar’s life, with all proceeds again going toward Super 30.

The incredible and unforeseen success of the book hasn’t changed Dr Mathew or Mr Kumar much. They both share a deep humility, possibly humility squared. They remain dedicated to their original chosen professions. Mr Kumar, the brilliant mathematician, continues to be an exceptional teacher, with a rare commitment to kids from the slums of India, and Dr Mathew continues to dedicate his time to his group practice and patients in Maple Ridge, to humanitarian activities, to clinical commitments at UBC, and to being the president of the BC Psychiatric Association.

While Dr Mathew’s first book may not parlay into another anytime soon, Super 30 and its success story is sure to inspire generations to come.

hidden

This article was written as a result of a presentation made at the BC Psychiatric Association’s October 2016 Educational Update. It has been peer reviewed.

hidden

Ms Lynch-Staunton is a sections coordinator with Doctors of BC.

I am a Canadian journalist based in Calgary, Alberta. I was wondering if you can share Dr. Mathew's ph. no. and email as I am interested in talking to him. My phone is 403-226-2214.

Thanks for your help.