The rise and fall of azithromycin for sexually transmitted infections

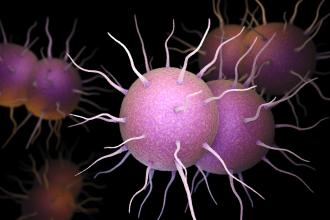

The rapidly growing use of new macrolide antibiotics such as azithromycin and clarithromycin in British Columbia and Canada has been associated with increasing levels of macrolide resistance in gram positive organisms, especially Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes (see the Figure).[1] S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is the most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia, and this organism is often implicated in acute otitis media, bacteremia, and meningitis. Furthermore, azithromycin resistance in Treponema pallidum (the causative organism for syphilis) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae have recently become a problem in BC and elsewhere. Antimicrobial resistance to azithromycin has grown hand in hand with its popularity as a broad spectrum antibiotic that is easy to administer in a single-dose oral formulation. Because of its long (96-hour) half-life in tissues, pathogen resistance is propagated by exposure to suboptimal concentrations for longer durations. For these reasons, azithromycin is no longer available in some northern European countries.

Since 1998 azithromycin has been provided free of charge by the BCCDC for the treatment of laboratory-confirmed cases of genital chlamydia infections and their contacts. In 2004, because of concerns around antibiotic resistance, doxycycline replaced azithromycin as the treatment of choice for uncomplicated urethral, cervical, and oral chlamydia, for non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU), and muco-purulent cervicitis (MPC), and as co-treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea.[2] Doxycycline and azithromycin are equivalent in every way for these sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment indications, including equivalent efficacy in randomized controlled trials and, perhaps more important to the practising clinician, these medications possess equivalent effectiveness in routine, front-line usage at public health clinics that serve marginalized populations such as adolescents, street youth, sex workers, and other street-involved populations.[2] In spite of the fact that azithromycin is given as single-dose oral therapy that can be directly observed by the clinician whereas doxycycline is prescribed as a twice daily oral capsule for 7 days, cure rates are identical and recurrences are equally unlikely.

This 2004 change in STI treatment recommendations was communicated by the STI/HIV Prevention and Control Division to the public health community, physicians, and clinics serving populations at risk and via a director’s letter to all who ordered free-of-charge STI drugs from the BCCDC pharmacy. There was also limited substitution of doxycycline for azithromycin in the filling of BCCDC STI drug orders. These measures resulted in a reduction in the proportional usage of azithromycin as chlamydia treatment from 75% to 45% with the doxycycline proportion increasing from 25% to 55%. However, the reduction in chlamydia usage for these indications has stalled in recent years and, as mentioned above, the prevalence of macrolide resistance has increased. Renewed measures to control the adverse effects associated with antibiotic resistance by restricting the usage of azithromycin are clearly needed now.

Since June 2009 the BCCDC’s STI Drug Order Request form has changed to reflect the concerns about azithromycin over-utilization and, when filling orders for free-of-charge STI medications, the BCCDC pharmacy has been substituting doxycycline for most of the azithromycin that has been requested. Azithromycin will continue to be first-line therapy for pre-abortion prophylaxis and, for this indication alone, azithromycin orders will continue to be filled as requested. The medical health officers of BC have given their support to this strategy.

Acknowledgments

Drs David Patrick and Fawziah Marra.

References

1. Epidemiology Services, BC Centre for Disease Control. Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in the Province of British Columbia—August 2008. www.bccdc.org/download.php?item=1785 (accessed 6 May 2009).

2. Rekart ML. Doxycycline: “New” treatment of choice for genital chlamydia infections. BC Med J 2004;46:503.

hidden

Dr Rekart is the director of STI/HIV Prevention and Control at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control.