Psychological preparedness for adverse events—A necessary addition to medical education

ABSTRACT: Adverse events in medicine are a frequent and unfortunate reality that can have a significant impact on patients and the physicians who care for them. This article provides an overview of the psychological impacts of adverse events and the role of anticipatory anxiety of such events on physicians and trainees. It draws from a medical student’s insights and experience in relation to current literature. I propose proactive psychological preparedness as a strategy to lessen the emotional impact of adverse events and promote resilience. This approach has potential benefits to patient safety, quality, and system improvements, and a reduction of the shame-and-blame medical culture.

Ensuring physicians and physician trainees are psychologically prepared for adverse events could benefit patients, physicians, and the health system itself.

In an interactive online seminar I attended in April 2021, our class of second-year University of British Columbia medical students was asked to share our three biggest concerns about our upcoming clinical clerkship. Some of the most frequently occurring answers were making mistakes, hurting a patient, and prescribing incorrectly. The speakers addressed each issue in turn. When it came time to speak to the concerns related to adverse events in medicine, students were given blanket reassurance that this was largely a baseless worry given the careful supervision provided by preceptors and other hospital staff. This response dismisses realistic concerns.

Adverse events in medicine is an immense topic, and medical errors are only one component. Although there is no absolute definition in the literature, adverse events are largely considered to be any unintended complication secondary to health care intervention.[1-3] According to a Canadian study published in 2004, 7.5% of patients experience at least one adverse event during admission to an acute care hospital, nearly two-thirds of which are not preventable.[1] We had several patient safety seminars during our preclerkship years, but the topics of medical errors and adverse events were minimally integrated into the curriculum. At the time, it was primarily a cautionary tale. I can recall a case-based learning session in my first year where the discussion turned to diagnostic errors, and the tutor stated we “would never work again” if we made such an error. Although it was an off-the-cuff remark, it was enough to strike fear into the hearts of even the most confident among us.

Patients are the primary victims of adverse events, but caring physicians may also be deeply affected.[4] Second victim syndrome, a term first coined by Albert Wu in 2000,[5] describes the psychological impact of adverse events on physicians and other health care providers. Feelings of shame, grief, and guilt are common hallmarks of second victim syndrome[6] and may lead to chronic mental illness and burnout.[7] The state of burnout has also been associated with predisposition to medical errors,[2,7] potentially leading to a cycle of harm for vulnerable physicians and the patients they care for.

While a subset of the literature describes adverse events as primarily medical errors secondary to human fallibility,[2,7,8] there is increasing recognition that second victim syndrome is more often related to a perceived failure, over any objective error.[9] Second victim syndrome can occur after poor response to treatment, a suboptimal outcome, unexpected death,[10] and negative social interactions with a patient or their family.[11] Persistence of the view that adverse events always stem from human error[12] promotes a culture in which physicians experience distress over events outside of their control. Examples of impacts unrelated to human error include resource limitations, long transport times, and unpredictable biological processes. To its credit, the UBC undergraduate medical education program has instilled the importance of reflective practice through regular portfolio sessions, which take the form of individual narrative medicine journaling exercises on difficult experiences in clinical practice followed by group debriefs. However, these mostly respond to past difficulties faced by students, rather than acting as a form of proactive psychological preparedness education.

In collaboration with a colleague, I continued to host informal narrative medicine nights for Northern Medical Program students during my training, where I was struck by the pervasiveness of difficult emotions, self-blame, an exaggerated sense of responsibility, and under-recognition of personal exemplary contributions, especially related to events involving patient death or suboptimal outcome. These experiences have also been documented in the literature,[9,10,13,14] as is the concerning reality that second victim syndrome often goes unrecognized.[15] People may also be unwilling to discuss their experiences openly without previous training due to overwhelming shame or fear of stigmatization.[10]

There is a potential opportunity in preclinical years to prepare trainees psychologically for adverse events and thereby inoculate them against second victim syndrome. While intervention may still be helpful after exposure to an adverse event, delay allows for negative thought patterns (rumination on guilt and self-blame) to become practised and automatic. The importance of preparing physicians and trainees for adverse events and how to recognize the impact of second victim syndrome have been expressed by other authors,[3,15] and recent literature indicates a clear need. In a study of nursing students in Korea, nearly a quarter had experienced an adverse event directly, while over three-quarters had experienced one indirectly.[16] Among Italian physicians and trainees, the incidence of involvement in an adverse event was nearly 15% in medical students and 44% in residents, with 66% of these physicians in training reporting symptoms of second victim syndrome.[17] Of respondents to a survey of Irish urology trainees, nearly 90% felt their training did not sufficiently prepare them for the impact of adverse events.[4] Proactive education may also help address the psychological toll that anticipatory anxiety of adverse events has on medical students.[18]

As is true for most psychotherapy, learning healthy strategies to cope with adverse events would be most effective in a euthymic state and would take time and repetition to achieve the best therapeutic benefit.[19] Therefore, early introduction during preclinical years is the obvious choice. Increased resilience also has implications for quality of care. Resilient physicians may feel less guilt for system- or circumstance-related adverse events (e.g., transport times, resource limitations, rural location), accepting an appropriate level of responsibility with a mental state less overwhelmed by emotion and more conducive to learning and professional development. If fewer physicians are devastated by second victim syndrome, occurrences of burnout will also be reduced, which will lead to better outcomes for patients and a reduction in further adverse events. This aligns with current concepts of safety in health care, where success is more than simply the absence of failure.[20] Supporting providers prior to adverse events also addresses the shame-and-blame culture that persists in medical environments[8] and helps to counter the view that guilt equates to caring. Healthy physicians less burdened by difficult emotions may also be better able to tackle system improvements, express empathy to patients, and provide support to others following an adverse event.

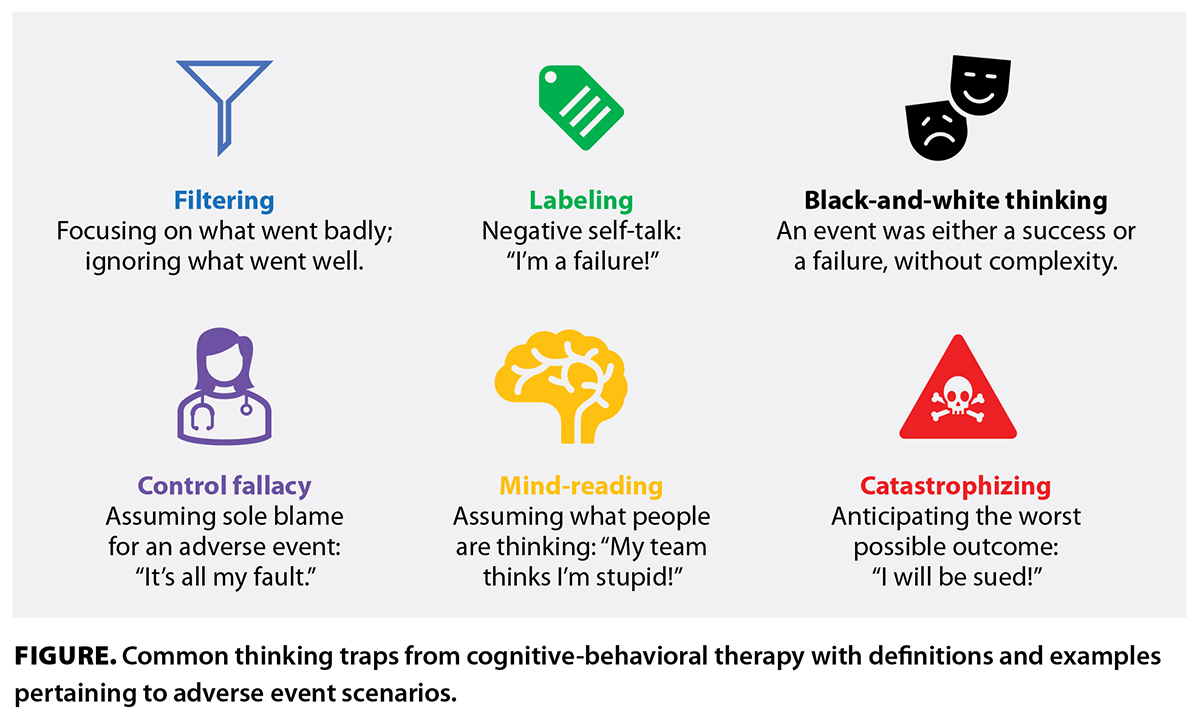

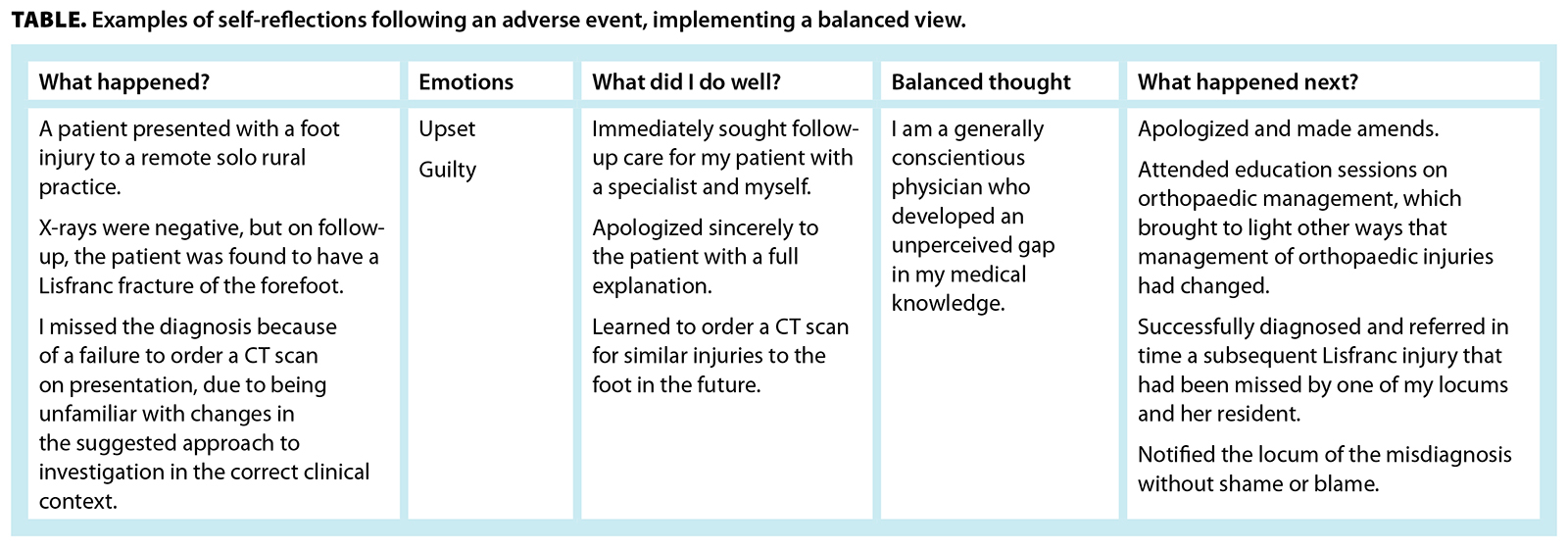

Over the past few years, I have collaboratively developed an educational seminar/workshop on preparation for adverse events, which was initially presented at the Rural Coordination Centre of BC’s Virtual BC Rural Health Conference 2021.[21] Further evaluation of this workshop has been made possible through a Rural Provider Preparation for Adverse Events grant, funded by the Rural Physician Research Support Project and sponsored by the Interior Health Authority. Ethics approval has been obtained, and the project was initiated in January 2024, with participants including physicians and medical, nursing, and social work students. The workshop was designed to introduce the topic of adverse events and provide tools and strategies to address them when they occur. It was held over Zoom and consisted of two groups of 15 participants, with opportunities for small-group learning, interaction, and time for questions and discussion. Our proposed tools are based on well-understood psychological principles that integrate with quality-of-care approaches. The tools include responsibility pie charts of positive and negative aspects of an adverse event, which allows learners to consider multiple factors, such as individual performance, team communication, and circumstance. We also provided strategies to develop a balanced view of performance [Table] and practised identifying common thinking traps [Figure] in stressful situations.

Over the past few years, I have collaboratively developed an educational seminar/workshop on preparation for adverse events, which was initially presented at the Rural Coordination Centre of BC’s Virtual BC Rural Health Conference 2021.[21] Further evaluation of this workshop has been made possible through a Rural Provider Preparation for Adverse Events grant, funded by the Rural Physician Research Support Project and sponsored by the Interior Health Authority. Ethics approval has been obtained, and the project was initiated in January 2024, with participants including physicians and medical, nursing, and social work students. The workshop was designed to introduce the topic of adverse events and provide tools and strategies to address them when they occur. It was held over Zoom and consisted of two groups of 15 participants, with opportunities for small-group learning, interaction, and time for questions and discussion. Our proposed tools are based on well-understood psychological principles that integrate with quality-of-care approaches. The tools include responsibility pie charts of positive and negative aspects of an adverse event, which allows learners to consider multiple factors, such as individual performance, team communication, and circumstance. We also provided strategies to develop a balanced view of performance [Table] and practised identifying common thinking traps [Figure] in stressful situations.

Our approach uses case studies to encourage guided application of tools, multidisciplinary physician and nurse participation, and emphasis on team functioning and the role of social support. Our highly adaptable tools can be used by individuals and teams and in peer-support settings. As this is a novel approach, we gathered pre- and post-intervention feedback from participants to assess the usefulness of this intervention. If this trial is a success, adaptation and dissemination to a wider audience of trainees will hopefully follow.

Adverse events will always occur in our health care system, whether because of the inherent fallibility of humans; the pressures on an underfunded system; or the difficulty of meeting the needs of a physically, spiritually, culturally, and economically diverse patient population spanning an immense area. It is time to introduce formal psychological preparation for adverse events because of the potential for improved patient care and, equally importantly, for the sake of our colleagues, friends, family, and ourselves.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to recognize Dr Brenda Griffiths, MD, FRCPC (Psych), for her ongoing mentorship and advice and Dr Kirstie Overhill, MD, CCFP, whose expertise in education and resilience work and development of novel concepts regarding advanced preparation for adverse events were invaluable to this article.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: The incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678-1686.

2. Heiss K, Clifton M. The unmeasured quality metric: Burn out and the second victim syndrome in healthcare. Semin Pediatr Surg 2019;28:189-194.

3. Carugno J, Winkel AF. Surgical catastrophe. Supporting the gynecologic surgeon after an adverse event. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2018;25:1117-1121.

4. O’Meara S, D’Arcy F, Dowling C, Walsh K. The psychological impact of adverse events on urology trainees. Ir J Med Sci 2023;192:1819-1824.

5. Wu AW. Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320:726-727.

6. Ozeke O, Ozeke V, Coskun O, Budakoglu II. Second victims in health care: Current perspectives. Adv Med Educ Pract 2019;10:593-603.

7. Marmon LM, Heiss K. Improving surgeon wellness: The second victim syndrome and quality of care. Semin Pediatr Surg 2015;24:315-318.

8. Clancy CM. Alleviating “second victim” syndrome: How we should handle patient harm. J Nurs Care Qual 2012;27:1-5.

9. Hu Y-Y, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: The case for peer support. Arch Surg 2012;147:212-217.

10. Davidson JE, Agan DL, Chakedis S, Skrobik Y. Workplace blame and related concepts: An analysis of three case studies. Chest 2015;148:543-549.

11. Klatt TE, Sachs JF, Huang C-C, Pilarski AM. Building a program of expanded peer support for the entire health care team: No one left behind. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2021;47:759-767.

12. Chen S, Skidmore S, Ferrigno BN, Sade RM. The second victim of unanticipated adverse events. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2023;166:890-894.

13. Seys D, Scott S, Wu A, et al. Supporting involved health care professionals (second victims) following an adverse health event: A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:678-687.

14. Harrison R, Lawton R, Perlo J, et al. Emotion and coping in the aftermath of medical error: A cross-country exploration. J Patient Saf 2015;11:28-35.

15. Chung AS, Smart J, Zdradzinski M, et al. Educator toolkits on second victim syndrome, mindfulness and meditation, and positive psychology: The 2017 Resident Wellness Consensus Summit. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:327-331.

16. Choi EY, Pyo J, Ock M, Lee H. Second victim phenomenon after patient safety incidents among Korean nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2021;107:105115.

17. Rinaldi C, Ratti M, Russotto S, et al. Healthcare students and medical residents as second victims: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:12218.

18. Nevalainen MK, Mantyranta T, Pitkala KH. Facing uncertainty as a medical student—A qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:218-223.

19. Parsons CE, Crane C, Parsons LJ, et al. Home practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of participants’ mindfulness practice and its association with outcomes. Behav Res Ther 2017;95:29-41.

20. Smaggus A. Safety-I, Safety-II and burnout: How complexity science can help clinician wellness. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:667-671.

21. MacDonald C, Overhill K. We can be very hard on ourselves when things do not go perfectly: Rural provider preparation for adverse events. Presented at the Rural Coordination Centre of BC’s Virtual BC Rural Health Conference 2021, Prince George, BC, 30 May 2021.

Dr MacDonald was a fourth-year medical student in the Faculty of Medicine in the University of British Columbia’s Northern Medical Program at the time this article was written. Her previous research was in medical anthropology at the University of Toronto, and she is a current R1 in family medicine at the University of British Columbia in Victoria, BC.

Great article on a crucially important topic. I am happy to see that this is going to be addressed in the Medical school training process as described. Keep up the good work.